This article explains acid-base analysis—specifically, how to interpret an Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) and Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP) to understand a patient’s acid-base status. The article may be of interest to medical students or clinicians interested in a step-by-step explanation of acid-base analysis, including situations where the pH appears normal. The article may also be of interest to data scientists or engineers who would like to learn more about how clinicians leverage laboratory testing for diagnosis. At the end, I’ve included a link to an open-source JavaScript implementation of the described process.

First, I’ll overview the ABG and BMP laboratory tests and explain the significance of blood pH. If you are clinical and already familiar with these concepts, feel free to skip the next three sections.

Arterial Blood Gas (ABG)

Many of us have had blood draws from veins, but an Arterial Blood Gas by definition must use arterial blood, which is usually obtained through the radial artery deep in the wrist. This is more painful than a venous blood draw because the artery is deeper and surrounded by more nerves.

ABGs can be life-saving tests because they provide key insights into a patient’s oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base status, and they help clinicians quickly diagnose and manage life-threatening conditions in the hospital.

In electronic health records, ABG results are usually displayed in a tabular format, but clinicians will often hand-write ABGs in a particular way:

pH / PaCO2 / PaO2 / HCO3 / SaO2 / BE

When handwritten, the name of the component is replaced by its numerical value for that patient, e.g.:

7.31 / 41 / 95 / 22 / 99 / 1

Here’s what the components mean:

- pH: a measurement of acidity or basicity

- PaCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen

- HCO3: bicarbonate

- SaO2: oxygen saturation

- BE: base excess

Basic Metabolic Panel

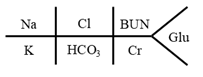

A BMP is typically handwritten with a fishbone structure:

Example with values:

The four electrolytes measured are:

- Sodium (Na)

- Chloride (Cl)

- Potassium (K)

- Bicarbonate (HCO3)

There are two markers of kidney function:

- Creatinine (Cr)

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN, read as B-U-N, not “bun.”)

Glu indicates blood glucose, which is blood sugar.

What is acid-base analysis, and why is it important?

The pH scale is used to measure the acidity or basicity of a substance. Acidic substances include oranges, lemons, vinegar, and sulfuric acid. Basic substances include egg whites, chalk, soap, toothpaste, baking soda, bleach, and oven cleaner.

The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14.

- A pH of 0 represents an extremely acidic substance (like battery acid).

- A pH of 7 is neutral (pure water).

- A pH of 14 represents an extremely basic substance (like drain cleaner).

The human body maintains blood pH in a narrow range: normal human blood pH is 7.35 to 7.45. Interestingly, this is the normal blood pH for most mammals.

Other parts of the human body have different pHs: stomach acid is very acidic, the small intestine is basic to neutralize stomach acid, and urine pH varies widely depending on diet and health.

The body has multiple mechanisms whereby it regulates blood pH, and multiple feedback loops that help keep blood pH between 7.35 and 7.45, primarily involving the lungs and the kidneys. A pH less than 6.8 or greater than 7.8 is typically lethal, meaning the tolerance is only about 0.4 units in either direction. It is therefore very important to correctly diagnose any acid-base disorders, because these disorders could be lethal and must be treated.

One critical lab test for understanding acid-base status is the pH. We can directly measure the pH of a patient’s blood.

- Sometimes, the pH is abnormal, indicating the patient has an acid-base disorder.

- A blood pH less than 7.35 is referred to as an “acidosis.”

- A blood pH greater than 7.45 is referred to as an “alkalosis.”

- Sometimes, the pH is normal because the patient is healthy.

- Sometimes, the pH is normal but the patient actually has one or more acid-base disorders.

- A process called “compensation” can occur, in which the body’s built-in feedback loops for regulating pH kick in and bring the pH closer to or within normal range. But compensation mechanisms cannot run forever. For example, hyperventilation can lead to respiratory muscle exhaustion, and kidney compensation can alter electrolyte levels, creating new risks. When compensation fails, the patient’s pH could abruptly dysregulate and the patient could die.

- A patient could also have more than one acid-base disorder at a time. Even though the pH might look normal at one point in time, the patient is still in danger, because one of the underlying conditions could suddenly worsen, leading to a change in pH that could kill the patient.

Therefore, even if the pH looks normal, it is critical to diagnose any acid-base abnormalities and treat the patient accordingly. But if the pH can be normal when there is actually a problem with acid-base status, how are we supposed to identify the problem?

The answer lies in acid-base analysis through a set of equations that help us interpret the ABG and BMP.

How this post came about

When I was in medical school, I felt uneasy about acid-base analysis. It seemed straightforward when the pH was normal, but I had a lingering sense of uncertainty around delta-deltas and delta gaps and how to handle situations where there were multiple disorders or compensation making the pH look normal.

After finishing medical school, while I was working on my health tech startup Cydoc, I decided we should implement a calculator that would automatically do acid-base analysis and show the differential diagnosis for any detected acid-base disorders. In order to write the code for this calculator, I had to take a deep dive into acid-base analysis and write out a clear algorithm for interpreting the lab test results. Now I’d like to share that algorithm in a blog post, in case it proves useful to others.

Disclaimer

The approach described here represents my own personal understanding of acid-base analysis. Always double-check with current guidelines and institutional protocols before making clinical decisions.

Obvious Acidosis (pH < 7.35)

First, we’ll consider cases where the pH is abnormal.

pH < 7.35 means the primary disorder is acidosis. But what kind of acidosis?

- If HCO3 < 22:

- Then the primary disorder is metabolic acidosis.

- Calculate expected compensation for metabolic acidosis:

- lower bound = 1.5 * HCO3 + 8 – 2

- upper bound = 1.5 * HCO3 + 8 + 2

- If the patient’s PaCO2 < lower bound, the secondary disorder is respiratory alkalosis.

- If the patient’s PaCO2 > upper bound, the secondary disorder is respiratory acidosis.

- If the patient’s PaCO2 is between the lower and upper bounds, then the patient’s PaCO2 is within the expected range, and there is adequate respiratory compensation. There is no secondary disorder.

- if PaCO2 > 45:

- Then the primary disorder is respiratory acidosis.

- Calculate expected compensation for acute respiratory acidosis:

- expected = 24 + 0.1 * (PaCO2 – 40)

- If the patient’s HCO3 < expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic acidosis.

- If the patient’s HCO3 > expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic alkalosis.

- If the patient’s HCO3 is equal to the expected value, then there is adequate metabolic compensation. There is no secondary disorder.

- Calculate expected compensation for chronic respiratory acidosis:

- expected = 24 + 0.35 * (PaCO2 – 40)

- If the patient’s HCO3 < expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic acidosis.

- If the patient’s HCO3 > expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic alkalosis.

- If the patient’s HCO3 is equal to the expected value, then there is adequate metabolic compensation. There is no secondary disorder.

You’ll notice that in this section, there are two possible options for compensation (the body’s feedback loops). We can use a compensation equation for an acute (short term) respiratory acidosis, or we can use a compensation equation for a chronic (long term) respiratory acidosis. Distinguishing which compensation equation to use fundamentally relies on the patient’s clinical timeline and presentation.

If the patient had sudden onset of symptoms (minutes to hours) in association with some acute events (like opioid overdose, inhaling an object, asthma attack) then this is more in line with an acute respiratory acidosis, and we’d use the compensation equations for acute respiratory acidosis. In this case the kidneys haven’t had time to help with compensation, since it takes 3 to 5 days for kidney-based compensation to work.

In contrast, if the patient has longstanding symptoms or a chronic condition (like known COPD, obesity hypoventilation, chronic neuromuscular disease), then we should use the compensation equations for chronic respiratory acidosis. The kidneys have had plenty of time to retain bicarbonate to help compensate, which is why the compensation equations are different in a chronic situation.

If you inspect the compensation equations for acute vs. chronic respiratory acidosis, you will see that all else being equal, the expected value of HCO3 in the chronic case is higher than in the acute case. This is “better compensation” because the kidneys have had time to kick in and do their hard work trying to bring the body closer to normal pH.

That’s it for low pH. Now let’s consider high pH:

Obvious Alkalosis (pH > 7.45)

pH > 7.45 means the primary disorder is alkalosis. But what kind of alkalosis?

- If HCO3 > 28:

- Then the primary disorder is metabolic alkalosis.

- Calculate expected compensation for metabolic alkalosis:

- lower bound = 0.7 * (HCO3 – 24) + 40 – 2

- upper bound = 0.7 * (HCO3 – 24) + 40 + 2

- If the patient’s PaCO2 < lower bound, the secondary disorder is respiratory alkalosis.

- If the patient’s PaCO2 > upper bound, the secondary disorder is respiratory acidosis.

- If the patient’s PaCO2 is between the lower and upper bounds, then the patient’s PaCO2 is within the expected range, and there is adequate respiratory compensation. There is no secondary disorder.

- If PaCO2 < 33

- Then the primary disorder is respiratory alkalosis.

- Calculate expected compensation for acute respiratory alkalosis:

- expected = 24 – 0.2 * (40 – PaCO2)

- if the patient’s HCO3 < expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic acidosis.

- if the patient’s HCO3 > expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic alkalosis.

- if the patient’s HCO3 is equal to the expected value, then there is adequate metabolic compensation.

- Calculate expected compensation for chronic respiratory alkalosis.

- expected = 24 – 0.4 * (40 – PaCO2)

- If the patient’s HCO3 < expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic acidosis.

- If the patient’s HCO3 > expected, the secondary disorder is metabolic alkalosis.

- If the patient’s HCO3 is equal to the expected value, then there is adequate metabolic compensation. There is no secondary disorder.

As before, the patient’s clinical context determines whether the equations for acute or chronic respiratory alkalosis are used. Acute respiratory alkalosis is often seen in short-term hyperventilation (e.g., panic attack, blood clot in the lung, salicylate poisoning, mechanical overventilation), while chronic respiratory alkalosis is often seen in sustained hyperventilation (e.g., living at high altitude, pregnancy, chronic liver disease, certain brain lesions).

Also as before, the compensation is expected to be “better” in the chronic case because the body has had more time to compensate.

Inspecting the algorithms above, the one for low pH and high pH, we can see they have parallel structure:

- First, we check the HCO3 value. If it’s past a certain threshold, we use compensation equations that give us a lower and upper bound for the patient’s PaCO2.

- Next, we check the PaCO2 value. If it’s past a certain threshold, we use compensation equations that give us an expected value for the patient’s HCO3. There are different compensation equations depending on whether we think it’s an acute process or a chronic process, a decision made based on clinical context.

Acid-base disturbances when the pH looks normal

Now we can move on to the tricker case: when there are acid-base disorders, but the pH appears to be normal (7.35 ≤ pH ≤ 7.45)

In this case, to understand what is going on with the patient, we can’t use the pH as a starting point. Instead, we need to calculate some other values, called the anion gap, the delta-delta (or delta ratio), and the delta gap. First, we’ll look at how to calculate these values, and then we’ll look at what they mean.

The equation for anion gap is simple:

calculated anion gap = Na – Cl – HCO3

Why is it called an “anion gap” and what is the concept behind this equation? An “anion” is a negatively charged ion. The body maintains electroneutrality, which is a balance between positive and negative ions. Na is positively charged, while Cl and HCO3 are negatively charged. The body’s ion balance can therefore be expressed as: Na = Cl + HCO3 + Unmeasured Anions. Here, “Unmeasured Anions” includes albumin (negatively charged at physiologic pH), phosphate, sulfate, and organic anions.

When we rearrange this balanced equation, we get: Unmeasured Anions = Na – Cl – HCO3, which is the same as the formula for the anion gap. So really, what we are doing with this anion gap equation is figuring out the quantity of unmeasured anions that this specific patient has at this moment in time.

Since albumin is such an important unmeasured anion, we can also calculate what anion gap we would expect the patient to have, based on their measured albumin level:

expected anion gap = 2.5 * albumin

(Yes, I did just sneak in one more lab test result, for albumin.)

We can then compare our calculated and expected values:

delta anion gap = calculated anion gap – expected anion gap

If this delta anion gap is a positive number, meaning our calculated anion gap > expected anion gap, then we have a high anion gap. This happens when there are additional unmeasured anions—often harmful acids, like lactate (seen in lactic acidosis), ketones (from diabetes complications or starvation), uremic acids (from kidney failure), or toxic alcohols (from accidental or purposeful ingestion).

Now we’ll calculate delta HCO3, representing how far away from normal our HCO3 is:

delta HCO3 = 24 – HCO3

And finally, we’ll calculate the delta-delta (also called delta ratio):

delta delta = delta anion gap / delta HCO3

This compares how much the anion gap differs from expectation with how much the bicarbonate differs from expectation. Here’s how to interpret the delta delta:

- if delta delta < 0.4, the patient has a NAGMA (non anion gap metabolic acidosis)

- if 0.4 ≤ delta delta ≤ 1, consider a combined HAGMA + NAGMA (where HAGMA is high anion gap metabolic acidosis)

- if 1 < delta delta < 2, the patient has a HAGMA

- if delta delta ≥ 2, consider combined HAGMA + metabolic alkalosis, or combined HAGMA + compensation for chronic respiratory acidosis

OK, we are almost done. There is just one more tool we have at our disposal for leveraging these lab test results to interpret the patient’s acid-base status. It’s almost the same as the delta delta, but we subtract instead of divide:

delta gap = delta anion gap – delta HCO3

Here’s how we interpret it:

- if delta gap < -6, consider combined HAGMA + NAGMA

- if -6 ≤ delta gap ≤ 6, the patient has a HAGMA

- if delta gap > 6, consider combined HAGMA + metabolic alkalosis

A quick note for non-clinical readers

Let’s take a step back now and think about the big picture here. Why on earth do we even care whether the patient has a HAGMA + metabolic alkalosis, or a respiratory acidosis with adequate compensation? It is just a jumble of tongue twisters?

We care because:

- There are multiple layers to diagnosis. The first layer (diagnosis of the specific acid-base disorder) is critical to the second layer (diagnosis of the underlying cause).

- We need to know both the first and second layers for proper treatment planning. Often the specific acid-base disorder can be treated directly (e.g., through infusions or changing ventilator settings). But even more importantly, we need to treat the underlying cause.

Differential Diagnosis

Here are examples of underlying causes/differential diagnoses for acid-base disorders:

Respiratory acidosis

- Pulmonary disease: COPD, asthma, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumonia, bronchitis, airway obstruction/foreign body aspiration, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, acute lung injury, pulmonary fibrosis, pleural effusion

- Decreased chest wall or diaphragm movement: obesity, diaphragmatic dysfunction or paralysis, neuromuscular disorders, Guillain-Barre, myasthenia gravis, demyelinating disorders, tetanus, muscle relaxants, organophosphates, botulism, acute chest trauma, chest wall deformity, tension pneumothorax

- Decreased respiratory drive: stroke, CNS tumor, encephalitis, CNS hemorrhage, medication use (opioids, alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, anesthetics)

Respiratory alkalosis

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), asthma, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, head trauma, heatstroke, hyperthyroidism, meningitis, myocardial infarction, panic disorder, pneumonia, pneumothorax, pregnancy, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sepsis, salicylate toxicity, theophylline toxicity

High anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA)

- GOLDMARK: glycols (ethylene glycol, propylene glycol), oxoproline (from excess acetaminophen), L-Lactate (lactic acidosis), D-Lactate (from gut bacteria), methanol (and other alcohols), aspirin/salicylate toxicity, renal failure (uremia), ketones (diabetic, alcoholic, starvation)

Normal anion gap metabolic acidosis (NAGMA)

- With any K: administration of IVF containing Cl-

- With high/normal K: administration of HCl (TPN, NH4Cl), hyperkalemic distal RTA (hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism, tubular resistance to aldosterone, aldosterone deficiency), chronic renal failure, Gordon’s syndrome, decreased distal Na delivery, drugs (triamterene, amiloride, pentamidine, NSAIDs, CEIs, ARBs, trimethoprim, spironolactone, heparin)

- With low K: diarrhea, intestinal fistulae, proximal RTA, distal RTA, ureteroileostomy, ureterosigmoidostomy, toluene intoxication, ketoacidosis, D-lactic acidosis

Metabolic alkalosis

- Hydrogen ion loss via vomiting, gastric secretion losses e.g. via NG suctioning, shift of hydrogen ions intracellularly from hypokalemia, bicarbonate administration, citrate in transfused blood, metabolism of ketoanions to produce bicarb, contraction alkalosis (loop or thiazide diuretic administration, diarrhea, or any excessive loss of volume), primary or secondary hyperaldosteronism, renal artery stenosis, Cushing syndrome, Liddle syndrome, Bartter syndrome, Gitelman syndrome, congenital chloridorrhea

The exact underlying disorder can be pinpointed by taking into consideration the patient’s history, physical exam, other lab test results (like drug tests or genetic tests), and/or imaging.

MDCalc Calculator

For clinical use, check out this MDCalc Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) Analyzer by Dr. Jonathan Chen.

Open-Source Implementation

For an open-source JavaScript implementation of the above algorithm, check out the repo rachellea/acidbase on GitHub. Someday I’d love to do a research study quantifying the utility of an acid base calculator built in to the EHR that automatically analyzes ABG and BMP results. If you’re a clinician or researcher in a health system and would be interested in collaborating on a research project like that, please send me a message via the Contact page.

Health AI Book

Want to be the first to hear about my upcoming book bridging healthcare, artificial intelligence, and business—and get a free list of my favorite health AI resources? Sign up here.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Angela Hemesath and Kenyon Wright who worked with me at Cydoc on the acid-base widget.

References and Additional Resources

General

- Evaluation of Acid-Base Disorders

- Acid-base disturbances in nephrotic syndrome (Kasagi et al. 2017)

- Physiology, Acid Base Balance (Hopkins et al. 2022)

- How to interpret arterial blood gas results

- Amboss: Acid-base disorders

Respiratory acidosis

- Respiratory Acidosis (Patel et al. 2023)

- BMJ Best Practice Respiratory Acidosis

- Medscape Respiratory Acidosis Differential Diagnoses

- Life in the Fast Lane Respiratory Acidosis DDx

Respiratory alkalosis

Metabolic acidosis

- Anion Gap and Non-Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (Kharsa et al. 2025)

- Differential Diagnosis of Nongap Metabolic Acidosis (Kraut et al. 2012)

- Approach to Patients with High Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (Fenves et al. 2021)

Metabolic alkalosis

- BMJ Best Practice Evaluation of metabolic alkalosis

- WikEM Metabolic alkalosis

- Life in the Fast Lane Metabolic Alkalosis

Delta Gap and Delta Ratio

- Time Of Care: The Delta Gap (is different from delta-delta or delta ratio)

- Time of Care: The Delta Ratio (delta delta): The delta anion gap / delta Bicarb Ratio

Featured Image by Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash